Transitioning From ISS to Commercial Space Stations: Plenty of Questions, But Few Answers

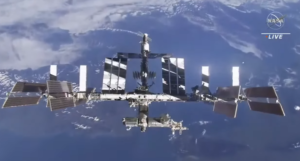

A congressional hearing today illuminated a wide range of policy issues awaiting resolution as the International Space Station nears its end, but the answers remain elusive. The ISS is expected to be decommissioned in 2030 and NASA is counting on the private sector to build new space stations in low Earth orbit, or LEO, where NASA can be just one of many customers. But timing is a challenge and the overriding concern is to avoid a gap between ISS and whatever comes next lest the only space station in LEO belongs to China.

The hearing before the space subcommittee of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee reasserted bipartisan support for the ISS. As subcommittee chairman Brian Babin (R-TX) pointed out, however, Congress now must plan “for a future that does not rely on the ISS.”

Subcommittee Ranking Member Eric Sorensen (D-IL) agreed it is a “consequential shift and we need to get it right.”

The first ISS modules were launched in 1998. Although a new Russian module was added as recently as 2021, construction was essentially completed in 2010 and the ISS is showing its age.

The 420-Metric Ton orbiting laboratory is a partnership among the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada, and 11 European countries working through the European Space Agency. While hailed as an engineering marvel and testament to international cooperation, there is no appetite for another government-led space station of this magnitude. The construction cost to the United States alone was on the order of $100 billion.

In recent years, NASA embraced Public-Private Partnerships to execute its human spaceflight program, including the crew and cargo vehicles that resupply the ISS and ferry astronauts back and forth. NASA now buys services from companies instead of owning and operating space vehicles. They want to do the same for replacing the ISS.

Through the Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program, NASA is providing some funding to incentivize the private sector to build their own space stations. NASA might be an anchor tenant at least in the early years, but the hope is that many other customers will emerge to close the business case through demand for everything from space research to space tourism.

Axiom Space and Voyager Space are two companies planning to build commercial space stations. At the hearing today, they raised a number of issues they and their investors want answers to as they proceed along that path.

Chief among them is an assurance they will not face competition from the government. NASA’s plan is to deorbit the ISS in 2030, but that date is not set in stone and they worry NASA might continue operating ISS even when their space stations are ready. They also worry Congress will not provide requisite initial funding, as well as about regulatory issues that need to be resolved.

Voyager Space’s Dylan Taylor was explicit. Voyager and Europe’s Airbus have a joint venture to build the Starlab space station, which will be launched by SpaceX’s Starship. He said Voyager is “committed to raising the majority of funding,” but U.S. government support is needed in five key areas.

“CLD must have U.S. government support in five key areas to assure investor confidence. First, the U.S. government is fully committed to utilizing continuously crewed space stations. Second, that the ISS will be decommissioned in 2030. Third, that Congress plans to adequately fund CLDs. Fourth, regulatory support for indemnification and liability concerns. And lastly, that the U.S. government will transition critical research to CLD platforms as they become available and not compete with industry.” — Dylan Taylor, Voyager Space

Axiom’s Mary Lynne Dittmar offered nine recommendations, including that Congress make clear it is U.S. policy to maintain continuous human presence in low Earth orbit “in perpetuity,” reinforce U.S. policy to encourage and enable fullest commercial use of space, and adequately fund the CLD program. In addition Axiom wants NASA to limit the number of companies in the CLD program to no more than two (currently there are three) and accelerate CLD contracts.

She was more nuanced about setting a specific end-date for ISS. Pointing out that unexpected developments like the COVID pandemic can disrupt supply chains and delay schedules, as has happened with their Axiom Station, they want ISS to continue through 2030 “with the possibility of extension until one commercial station is operational.”

“Having an uncertain end date for the International Space Station is really detrimental to commercial development of low Earth orbit because it creates a great deal of uncertainty with regard to investors [but] one of our recommendations is that it does stay in orbit until there’s a commercal platform … [but] not one second longer. Not one second longer.” — Mary Lynne Dittmar, Axiom Space

Ken Bowersox, NASA Associate Administrator for Space Operations, argued that deorbiting ISS should not be driven by schedule because of the importance of ensuring there is no gap between the end of ISS and the availability of new U.S.-led space stations. He wants agreed-upon criteria for when deorbit should happen instead of a specific date.

“I think we can set some criteria for the transition, agree on some criteria for the transition, be bound by those criteria, perhaps rather than dates, but I want to emphasize our commitment to switching to the commercial destinations.” — Ken Bowersox, NASA

The goal of avoiding a gap pervaded the hearing, not only because NASA wants a seamless transition for its own microgravity research, but to make sure China is not the only country with an Earth-orbiting space station.

China now is operating the 68-Metric Ton Tiangong-3 space station. The first module was launched in 2021 and two more were added in 2022. They began permanent occupancy with regular crew rotations at the end of 2022. That’s 22 years later than when permanent occupancy of the ISS started in November 2000 and although it’s much smaller and with more limited capabilities than ISS it has the advantage of being new.

Almost every subcommittee member raised the China issue, as did witnesses. Taylor said Tiangong-3 “is an immediate risk to U.S. leadership in space, science, and technology as they are operating a platform that is decades more modern than today’s ISS.” Dittmar cautioned that “if we have a gap of American presence in low-Earth orbit, the only winner will be China.”

Another issue is what regulations the government will require for commercial space stations and which agency should oversee them. The committee approved legislation in November on a party-line vote that would put the Department of Commerce in charge of “mission authorization” including in-orbit operations like space stations. However, the White House has a different proposal splitting mission authorization between DOC and the Department of Transportation.

As that’s debated, companies like Voyager and Axiom need to know about liability, indemnification, and insurance requirements. Taylor said NASA’s use of commercial space stations “will require new approaches to insurance and liability risk sharing agreements with the U.S. government and international agencies.”

Full committee Ranking Member Zoe Lofren raised a completely different regulatory issue — regulation of non-government funded research conducted on private space stations. Citing a recent article in Aerospace America, “The ‘Wild West’ of Space Research,” that described a Dutch company’s proposal to “grow a baby in space,” Lofgren pointed out that “unless you have public funds in the research, pretty much there aren’t any regulations. You can do what you want.”

Bowersox replied that NASA does not want to put constraints on what the companies do, but “if something really exceeded what we thought were the boundaries of our ethical standards, then we would have a long talk.” Taylor said Voyager would follow all NASA requirements and they will be integrating their science payloads at their George Washington Carver Science Park in Ohio that will be subject to U.S. law and regulation.

Dittmar said Axiom’s Chief Scientist, Lucie Low, was one of several authors of a recent article on this subject. That article called for setting ethical guidelines before human research is conducted as part of commercial human spaceflight.

University of Florida Distinguished Professor Robert Ferl, who co-chaired last year’s Decadal Survey on Biological and Physical Sciences in Space from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and was testifying as co-chair of the Academies’ associated committee, replied only that the “scientific question” of whether terrestrial organisms can develop in space as they do on Earth already has been answered affirmatively. “The scientific basis for what you are discussing wouldn’t necessarily fall into our realm,” but “scientists are by and large excruciatingly ethical.”

Underpinning the discussion about the future of ISS and future space stations is how much money Congress will appropriate for the CLD program not just for FY2024, but in future years. The request for FY2024 is $228 million, but House Republicans are demanding dramatic cuts to non-defense government spending, which includes NASA. NASA’s request shows a projected request of $230 million for FY2025, but Dittmar and Taylor asked the committee to authorize $295 million.

CLD funding is on top of the roughly $3 billion a year needed for ISS operations and NASA is also asking for $1 billion over the next several years ($180 million in FY2024) to build a space tug to safely deorbit the ISS into the Pacific Ocean.

Dittmar stressed there is “no clear path” to getting the funding required to ensure a successful transition from the ISS to commercial space stations “putting the transition under threat and opening the door to losing leadership to China in the event of a gap.”

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.