Mars Sample Return Gets a Lifeline from House Appropriators

The House Appropriations Committee delayed markup of the FY2026 Commerce-Justice-Science bill that was scheduled for today, but released the report detailing how the committee wants NASA to spend the $24.8 billion recommended by the CJS subcommittee last week. That would keep NASA at its current spending level and is $6 billion more than proposed by the Trump Administration. Among the many differences is continued funding for the Mars Sample Return mission that the Administration wants to terminate. Congressional staffers at a National Academies meeting today expressed concern, however, about whether money Congress appropriates will be spent as intended.

The House Appropriations CJS subcommittee approved the bill on July 15 and released the text and a summary, but the report contains many more details. Like its Senate counterpart, the House subcommittee rejects the Trump Administration’s proposal to cut NASA by 24.3 percent, from $24.8 billion to $18.8 billion. The totals recommended by the two committees are similar — $24.8 billion in the House, $24.9 billion in the Senate — but the specifics are different in many cases, including the future of Mars Sample Return (MSR).

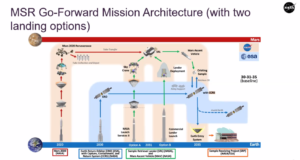

The Senate report doesn’t mention MSR at all. Two years ago the Senate committee was first to raise concerns about the growing pricetag for the NASA-ESA mission to bring back to Earth samples being collected right now by NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover. NASA paused the program to look for new ideas. As the Biden Administration came to an end in January, NASA’s leadership said they’d leave it to the next administration to decide how to proceed. A key decision would be whether to use heritage NASA systems or new commercial systems to deliver the landing platform and rocket needed to boost the samples into Martian orbit.

The Trump Administration chose neither. The budget request would terminate the program with NASA directed to “pivot to lower-cost, competitively selected Mars science missions that can complement our long-term human exploration goals.”

The House subcommittee disagrees, providing $300 million “to advance the mission and maintain U.S. leadership in planetary science,” noting that China is planning to launch its own Mars sample return mission in 2028. The subcommittee adds that MSR is developing capabilities “critical to the success of human exploration of the Moon and Mars” and directs NASA to coordinate efforts between the science and exploration mission directorates to advance those technologies. They acknowledge commercial partnerships could be beneficial at lowering cost and accelerating the mission and require a report from NASA 30 days after the law is enacted to report on the potential of those partnerships.

MSR is part of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD). The Trump Administration wants to cut SMD by 47 percent, from $7.3 billion to $3.9 billion. The Senate committee maintains total funding at $7.3 billion and specifically identifies a large number of programs it does not want terminated, including many operating missions.

The House subcommittee cuts SMD to $6 billion and is less explicit about which programs should continue, but is broadly supportive. Among those that get shout-outs other than MSR are the ESA-led Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) gravitational wave detector, the OSIRIS-APEX mission to study asteroid Apophis after it makes a close pass of Earth in 2029, and Earth System Observatory missions. Support for NASA’s participation in ESA’s Rosalind Franklin Mars rover mission, which is included in the Senate committee’s bill, is not mentioned here.

The House subcommittee provides less for science and NASA’s other accounts than the Senate because their focus is exploration. Exploration fares well in the Administration’s budget request with an increase from $7.7 billion in FY2025 to $8.3 billion in FY2026, but the House subcommittee goes further recommending $9.7 billion.

The report language doesn’t shed much light on how the subcommittee wants the extra $2 billion spent, but does make clear support for the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft that will take astronauts to lunar orbit as well as the Gateway lunar space station, all part of the Artemis program. The Administration wants to terminate SLS and Orion after the Artemis III mission, currently planned for mid-2027, and replace them with commercial alternatives. It sees no need for Gateway.

The House and Senate committees are aligned in continuing their historical support for SLS and Orion. Congress directed NASA to build those systems in the 2010 NASA Authorization Act after President Obama canceled the Constellation program, Artemis’s predecessor. SLS is harshly criticized by SpaceX’s Elon Musk and others because it is not reusable and is very expensive, but it is the only rocket capable of sending people to the Moon today. Musk’s Starship and other rockets in development may be able to do that in future, but are not ready now.

The current version of SLS, Block I, flew successfully in 2022 on the Artemis I uncrewed test flight and will be used for the next two flights: Artemis II in 2026 that will send four astronauts (three American, one Canadian) around the Moon on a crewed test flight and Artemis III in 2027 that will land astronauts on the Moon for the first time since 1972.

SLS flights after that will use a more capable version, Block IB, developed pursuant to congressional direction in the 2010 Act. Block IB will have a new Exploration Upper Stage (EUS). Because it is taller and heavier, a new Mobile Launcher, ML2, is also needed. The House subcommittee directs NASA to “evaluate alternatives” to the current EUS design, including “commercial and international collaboration opportunities” to reduce costs and shorten the schedule. NASA still must maintain the lift capacity of 130 Metric Tons to low Earth orbit as required in the 2010 Act, however. NASA has 180 days after the bill’s enactment to report back on its findings.

Both committees support Gateway as well, being built by the U.S., Europe, Canada, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates.

In addition to appropriations, Congress provided billions for SLS, Orion and Gateway in the reconciliation bill.

The Moon isn’t the only destination Congress has in mind for astronauts. Using language very similar to what’s in the Senate committee’s bill, the House subcommittee “strongly supports” NASA’s goal of sending humans to Mars and directs NASA to prioritize development of commercial systems capable of taking cargo, and someday crews, to Mars. They want an initial system demonstration the next time Earth and Mars are properly aligned, which is at the end of 2026.

Mars — The Committee recognizes that it has long been NASA’s priority human exploration goal to safely land American astronauts on Mars, and it strongly supports NASA’s renewed efforts to accelerate this objective and reduce costs by maximizing commercial innovation and fixed-price development partnerships followed by commercial service procurements. The ability to launch from Earth and land large cargo on the Martian surface is vital to enabling both crewed and uncrewed missions. Of the amounts made available for Mars exploration, NASA shall prioritize and accelerate the development of commercial systems capable of performing entry, descent, and landing of human class cargo and later crew on Mars, with a goal of [a] launching an initial system demonstration to Mars by the 2026 Earth-Mars transfer window.

Like the Senate committee, there is no indication of how much money is “made available for Mars exploration.” The Administration’s budget request includes $1 billion for Mars in the exploration account.

The House subcommittee continues its strong support for developing Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) with $175 million, as well as Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP), which gets $80 million.

Among other interesting provisions, the House subcommittee includes $5 million “for modification and certification activities necessary to convert a U.S. commercial cargo reentry vehicle to safely reenter and land crew on a runway within the continental U.S.” as an “emergency crew return capability.” The only existing commercial cargo vehicle designed to survive reentry is SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon, which splashes down in the ocean, but Sierra Space is developing Dream Chaser, which will, in fact, land on a runway. Dream Chaser looks like a small space shuttle. In 2014 Dream Chaser lost out to SpaceX’s Dragon and Boeing’s Starliner in the commercial crew competition, but Sierra Space has been developing it as a commercial cargo vehicle for now with aspirations to use it for crew someday. It was awarded six flights in NASA’s 2016 CRS2 commercial cargo competition, but the first flight has been repeatedly delayed.

The bottom line is that House and Senate appropriators clearly support NASA at its current funding level, not the $6 billion reduction proposed by the Trump Administration. On top of $24.8 billion or so appropriators want to provide, the reconciliation bill includes another $10 billion. That spending isn’t all in FY2026, however, but spread over several years.

The looming question is whether the Administration will spend the money the way Congress appropriates it.

At a meeting of the Space Studies Board (SSB) and the Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board (ASEB) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine today, four congressional staff members from both parties and both sides of Capitol Hill conveyed caution about the murky funding road ahead.

For example, Congress has not been provided with the usual spending plan detailing how the money appropriated for FY2025 is being spent. Earlier in the meeting, Acting NASA Associate Administrator Vanessa Wyche confirmed the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is providing money to NASA 30 days at a time.

Pamela Whitney from the House Science, Space and Technology Committee’s Democratic staff said she’s never heard that 30-day incremental funding is “the way programs operate best.” There’s also concern that OMB is impounding (not spending) appropriated funds and NASA is beginning to close down programs as though the FY2026 budget request was adopted even though Congress hasn’t acted on it yet.

Basically agencies cannot be certain they will be able to spend the money Congress provides. House SS&T Republican staffer Brent Blevins noted that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found a second instance of impoundment this morning regarding Head Start programs. Impoundment is illegal under the 1974 Impoundment Act. Blevins thinks the issue ultimately will end up at the Supreme Court.

The uncertainty applies to the reconciliation bill as well. Maddy Davis from the Republican staff of the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee, which wrote the NASA section of the reconciliation bill, said they haven’t seen the “spend plan” for that yet either. She says they look forward to “a very positive, collaborative experience with [OMB] to make sure that those funds are dispersed in the way that we intended them to be.”

The first challenge is getting appropriations bills passed. The House began its summer break yesterday, a day earlier than expected, which is why the full committee CJS markup was postponed. A new date wasn’t announced. So far the House has passed only two appropriations bills: Military Construction/Veterans Affairs (MilCon/VA) and Defense.

That’s two more than the Senate, although the Senate will be in session for at least one more week and is teeing up three bills, including CJS, for joint consideration. Whether they’ll complete action on the bills — MilCon/VA and Agriculture are the other two — before they depart for recess is an open question. There are 12 appropriations bills all together that need to pass.

Both chambers return on September 2 with little time before FY2026 begins on October 1. A Continuing Resolution (CR) seems all but certain. Senate Commerce Democratic staffer Dave Turner said if it was a “normal CR situation” the space community might be happy with that because it would hold NASA at its current funding level, but “the risk of impoundment is there,” which is a “serious concern.”

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.