Boeing Warns of Potential SLS Layoffs

Boeing told employees working on the Space Launch System program yesterday that significant layoffs may take place by April because of anticipated changes by NASA. They added they would try to minimize job losses by redeploying personnel.

In a statement to SpacePolicyOnline.com, Boeing said there is a potential for 400 fewer positions on the SLS program and they are informing their workforce in compliance with the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act.

As first reported by Ars Technica, Boeing Vice President and Program Manager for SLS David Dutcher notified the SLS team that some contracts could end as soon as next month.

Speculation is rampant about what the new Trump Administration will do with NASA’s Artemis program to return astronauts to the lunar surface. Although there has been concern that the entire program might be redirected to focus on sending people to Mars instead, President Trump and Japanese Prime Minister ISHIBA Shigeru just reaffirmed their commitment to joint lunar surface exploration yesterday.

But even if Artemis continues to focus on the Moon, what rocket or rockets should be used to transport astronauts back and forth is a matter of intense debate.

Congress directed NASA to build SLS in the 2010 NASA authorization act after President Barack Obama canceled the George W. Bush Administration’s Constellation program to get astronauts back to the Moon by 2020. Under Constellation, NASA was building a big new rocket, Ares V, plus a smaller version, Ares I, as well as a crew capsule, Orion. Bush had also directed that the space shuttle program be terminated when construction of the International Space Station was completed around 2010, so Ares I/Orion would transport crews to and from the International Space Station, while Ares V/Orion would send them to the Moon.

With all of that canceled, in addition to the space shuttle, Congress was concerned about the loss of jobs and the impact on the industrial base. In the 2010 act, they required NASA to build a big new rocket anyway and a Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) to go with it. SLS became the rocket. Orion was retained as the MPCV.

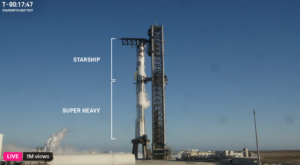

In 2010, commercial rockets for sending people to the Moon weren’t on the radar. Apart from the space shuttle, the United Launch Alliance’s Delta and Atlas rockets were the mainstay of the U.S. rocket fleet. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 only had its first launch that year and Falcon Heavy wouldn’t fly until 2018. That’s about the same time the public started hearing about SpaceX’s plans for the Big Falcon Rocket, now known as Starship, which is in the testing phase today.

Times are changing and a reassessment is underway. SLS is years late and significantly over cost. It has flown only once — the Artemis I uncrewed test flight in November 2022. The second launch, Artemis II, has been repeatedly delayed and is currently targeted for April 2026, three-and-a-half years after the first. While much of the delay is due to the Orion capsule, not SLS, the costs for SLS keep rising not only for the current version, Block I, but the more capable Block IB under development.

Boeing is the prime contractor for the SLS system and builds the Core Stage (orange) for Block I. For Block IB, it is also building a bigger Exploration Upper Stage (EUS). Because it’s taller and heavier, Block IB needs a stronger Mobile Launcher, ML-2. Bechtel is the prime contractor for ML-2 and came under withering criticism from then-NASA Administrator Bill Nelson in 2022 for overruns and delays.

Multiple reports from the Government Accountabilty Office and NASA’s Inspector General over many years have harshly criticized NASA’s management of the SLS program, especially the ML-2 contract.

At the moment, however, there is no commercial alternative to SLS. SpaceX’s Starship is making progress, but is still in the testing phase. The second stage exploded over the Caribbean Ocean on the most recent Integrated Flight Test-7.

SpaceX is under contract to use Starship as the Human Landing System for Artemis III, the first time astronauts will land on the Moon’s surface since the Apollo program, now scheduled for 2027. Whether the White House and NASA would want to abandon SLS and put their eggs in Starship’s basket for that mission remains to be seen, but many expect that future upgrades to SLS, like Block IB or the even larger Block II, are at risk.

Other large commercial rockets are available or coming online — SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, the United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan, and Blue Origin’s New Glenn — but they cannot launch as much mass to a Trans-Lunar Injection (TLI) trajectory as SLS. In fact, Starship and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lunar lander both rely on in-space refueling to make the trip to the Moon and in-space fuel depots don’t exist yet. They have the advantage of being reusable, however. SLS is not.

Although Boeing made this announcement yesterday, the White House and NASA have not revealed their plans for Artemis.That’s expected to come as part of Trump’s FY2026 budget submission. A top-level “skinny” budget could come out in early March, with a detailed proposal weeks later.

Whatever they propose, Congress will have to decide whether or not to agree. SLS has had strong support for all these years in Congress. Just as workforce impacts led to the creation of SLS in the first place, they could sustain it now. Boeing is the prime contractor, but workers in many other companies would be affected if the program is terminated entirely. Northrop Grumman builds the Solid Rocket Boosters, Aerojet Rocketdyne (an L3Harris Technologies company) the engines, and the United Launch Alliance provides the second stage for the current version (the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage — ICPS). In addition a number of companies are part of Exploration Ground Systems that support the SLS program including Amentum (formerly Jacobs).

This article has been updated.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.