NASA Will Finalize Mars Sample Return Architecture Next Year

NASA will wait until the middle of next year to decide on the fastest, cheapest way to get the samples now being collected on Mars by the Perseverance rover back to Earth. Agency officials said today they will continue engineering studies of two options, one using an upgraded version of JPL’s sky crane and the other a commercial “heavy lander,” to determine which will get the samples here soonest at the lowest cost.

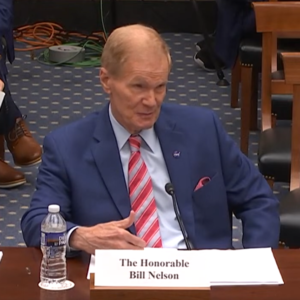

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson directed a pause in the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program last spring when the projected cost mushroomed to $11 billion while the date for when the samples would be back on Earth slipped to the 2040s.

He invited industry, NASA field centers, and JPL, a Federally-Funded Research and Development Center (FFRDC) operated for NASA by the California Institute of Technology, to propose ideas on how to do it cheaper and faster. Today’s announcement is the result of an independent assessment of those proposals by a Mars Sample Return Strategic Review team led by MIT’s Maria Zuber.

The estimated costs for the two options range from $5.8-$7.7 billion with the samples on Earth in the mid-late 2030s instead of the 2040s.

Emphasizing that sufficient funding is at the root of whatever MSR mission is pursued, Nelson stressed that a minimum of $300 million is needed in the current fiscal year, FY2025, to enable a decision next year. Congress hasn’t completed action on FY2025 appropriations even though the fiscal year began on October 1.

That money is needed to enable engineering studies of the best way to get a lander on Mars with a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) that can boost the samples into orbit around Mars.

NASA and ESA are partners on the MSR program. It’s a three-part mission: collect a scientifically-selected set of samples with NASA’s Perseverance rover that tell the story of Mars’ past including whether it might once have harbored microbial life; transfer the samples onto a rocket (the MAV) that sends them into orbit; and then transfer them into ESA’s European Return Orbiter (ERO) for the trip to Earth.

That’s been the top-level architecture for years and the first and third steps are largely unchanged, but the middle step — getting the samples collected by Perseverance onto a MAV and launching it to orbit — is problematic.

Perseverance’s companion, the Ingenuity helicopter, was the first spacecraft to lift off from Mars, but the highest it flew during its 72 flights was 79 feet (24 meters). The MAV will have to reach orbit, the first such attempt from a planet with one-third Earth’s gravity and a vanishingly thin atmosphere.

NASA has made some decisions about the MSR reboot already.

Perseverance will drive itself over to the lander and a robotic arm will transfer the 30 samples of Martian material in cigar-shaped tubes into the MAV. In the earlier plan, helicopters derived from Ingenuity would fly over to a cache of 10 samples deliberately left in Jezero Crater and bring them to the lander in case Perseverance was unable to make the trip. NASA now believes Perseverance will be in good shape so the helicopters aren’t needed and only the 30 samples on the rover, not the 10 at Jezero, will come back. They’ll use an existing design for the robotic arm instead of developing a new one. They’ll change the sample-loading system to avoid getting dust on the sample container to ameliorate planetary protection requirements and negate the need to clean the tubes when they’re on the orbiter. They also will use a Radioisotope Power System (RPS) instead of solar arrays for the lander so the system can operate during dust storms and keep the MAV’s solid rocket motors warm.

Europe will still provide the ERO to transport the samples from Mars to Earth.

What is undecided is the size of the lander and how to get it onto the surface. The lander has to be big enough to accommodate the MAV. The size of the MAV is dependent on how much mass it must lift into orbit.

NASA will evaluate two options between now and the middle of 2026.

Option 1, with a projected cost of $6.6-$7.7 billion, is to use an upgraded version of JPL’s sky crane that landed the Mars Curiosity rover in 2012 and Perseverance in 2021 during what JPL dubbed “7 Minutes of Terror.” Nicky Fox, NASA Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, said the sky crane for this mission will have to be about 20 percent bigger.

Option 2, estimated to cost $5.8-$7.1 billion, is to use a commercially-provided “heavy lander.” Fox declined to provide specifics because the proposals submitted by various companies are proprietary.

Both options envision launching ESA’s ERO in 2030 and NASA’s lander/MAV in 2031, with the samples returning to Earth in the 2035-2039 time frame, but Nelson repeatedly said the schedule is dependent on funding.

Nelson and Fox said they looked at the option of sending the samples to cislunar space instead of directly back to Earth as some suggested, but decided against it because it adds cost and complexity.

Asked if he’s concerned about getting samples back from Mars before China does, Nelson made the point that China plans to return “grab and go” samples — whatever they can pick up from wherever they land — not the carefully collected scientific samples that can tell the story of Mars’ history and whether life once existed there.

“You cannot compare the two. Ours … is an extremely well thought out mission created by the scientific community of the world as to what are the various sites in and around Jezero Crater that will give us a picture of the historical record, millions of years ago, when there was water there. …

“You compare that to at least what has been said publicly by the Chinese government and that is that they’re just going to have a mission to grab and go. Go to a landing site of their choosing, grab a sample, and go. That does not give you the comprehensive look for the science community. So you cannot compare the two missions. Now will people say that there’s a race? Well, of course people will say that. But it’s two totally different missions.” — Bill Nelson

How fast the United States can go depends on funding and what happens next depends on the Trump Administration. He hasn’t had any discussions with them, but “I think it was a responsible thing to do, to not hand the next Administration just one alternative if they want to have a Mars Sample Return mission. Which I can’t imagine they don’t. I don’t think we want the only sample return coming back on a Chinese spacecraft.”

This article has been updated.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.