NASA Copes with Details of $6 Billion Budget Cut, Leadership Uncertainty

The Trump Administration sent the full FY2026 budget request to Congress late Friday spelling out the details of the $6 billion (24.3 percent) cut to NASA revealed in the May 2 “skinny budget.” The request drives home the point that human spaceflight now outweighs everything else at NASA, a sea-change from an era when science had an almost equal seat at the table. On top of that, yesterday’s decision by President Trump to withdraw the nomination of Jared Isaacman to be NASA Administrator adds uncertainty. The White House said a replacement will be announced soon, but whoever it is still must go through the confirmation process, keeping the agency in limbo.

After a decade of rising budgets, Congress pushed NASA a step backward in FY2024 and FY2025, but the FY2026 budget request would be a steep dive from $24.8 billion to $18.8 billion and staying there through FY2030 with no adjustment for inflation.

Every part of the agency would suffer deep cuts except human spaceflight. Even there, phase-out of the International Space Station would begin much earlier than expected and the Artemis program as currently planned would end after Artemis III when astronauts land on the Moon for the first time since Apollo. A Moon-to-Mars program would endure, but how much it would resemble NASA’s current plan is unclear.

The sweeping changes are difficult to grasp and NASA is far from alone. Except for national security, border control, energy, and extending/broadening tax cuts, the Trump Administration and many Republicans in Congress are determined to cut federal spending dramatically. Science appears to be a target. In terms of percentages, NASA’s cut is far less than the 55 percent reduction proposed for the National Science Foundation. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) would lose nearly 40 percent, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) 27 percent, and the Office of Science in the Department of Energy 14 percent.

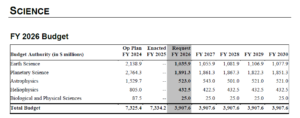

At NASA, the requests for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate (ESDMD), which oversees the Moon-to-Mars program, and the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) exemplify the stark contrast between the Trump Administration’s warm embrace of sending humans into deep space and cold shoulder to science.

For starters, ESDMD gets a $647 million increase while SMD suffers a $3.426 billion decrease.

In ESDMD, the budget heralds an investment of “more than $1 billion in new funding to put the nation on a path to land the first humans on Mars.” It retains the strategy of returning astronauts to the Moon before heading to Mars, though, a relief to those who feared Trump’s enthusiasm for Elon Musk’s vision of making humanity a multi-planetary species meant a pivot away from the Moon. It’s still Moon-to-Mars, not just Mars.

Putting astronauts back on the Moon and creating a sustainable human presence there is the point of the Artemis program, but its future is unclear. One major change is elimination of the Gateway lunar space station that was to serve as the transit point for astronauts between Earth and the lunar surface. Another is cancellation of NASA’s SLS rocket and Orion crew spacecraft designed to ferry astronauts between Earth and lunar orbit. They’ll be used for the Artemis II mission next spring to take four astronauts on a test flight around the Moon and the Artemis III lunar landing mission a year later, but that’s it.

SLS is often criticized because it suffered long developmental delays and is expensive, but right now it’s the only rocket on Earth capable of sending people to the Moon. As many point out it’s not reusable, but then again it doesn’t require in-space refueling. Sending a spacecraft like Orion to lunar orbit on SLS is a non-stop flight.

Other rockets like SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn are in development and have been selected to serve as the Human Landing Systems for Artemis crews to get from lunar orbit to the surface and back. The budget proposal calls for a competitive process to choose an SLS replacement to get to lunar orbit and both are expected to be top contenders, but they’re experiencing their own delays. Starship just suffered its third RUD (Rapid Unscheduled Disassembly) in a row and hasn’t attempted to enter orbit yet. New Glenn has only flown once to Earth orbit, not to the Moon. Both require in-space cryogenic refueling to reach the Moon, which hasn’t been demonstrated yet. They are reusable, but how much money NASA will save remains to be seen since the SLS/Orion development costs are largely in the past and the cost-per-launch was expected to go down with a regular cadence of flights. SpaceX and Blue Origin are privately held so the development costs for Starship and New Glenn aren’t publicly known, nor is the price they’ll charge NASA. Perhaps more importantly is uncertainty as to when either system will be ready to carry people. Whether switching horses midstream before another horse is alongside turns out to be a winning strategy remains to be seen, although either Starship or New Glenn and its Blue Moon MK2 lander will have to be ready before a lunar landing can occur.

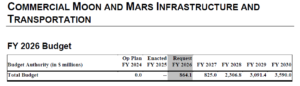

ESDMD would see a stronger focus on the Mars portion of the Moon-to-Mars program. A new “Commercial Moon and Mars Infrastructure & Transportation” line item gets $864 million of ESDMD’s $8.3 billion in FY2026 and quickly ramps up thereafter. The category includes a new “Mars Technology” line that gets $350 million in FY2026 and $500 million per year thereafter.

By contrast, SMD would lose 47 percent, with reductions across all five disciplines: astrophysics, biological and physical sciences, earth science, heliophysics, and planetary science. The budget acknowledges that “NASA’s science missions have greatly expanded humanity’s understanding of the Earth, solar system, and universe,” but asserts that spending “over $7 billion per year on over 100 missions is unsustainable.”

Examples of what’s in and what’s out include the following:

- Astrophysics

- In: NASA-ESA Hubble Space Telescope (visible wavelengths), NASA-ESA-Canada James Webb Space Telescope (infrared), SPHEREx (near infrared), upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (infrared wide-field-of-view).

- Out: Chandra Space Telescope (x-ray), XRISM telescope (x-ray, with Japan), NICER, Swift, upcoming Ultra Violet Explorer (UVEX), astrophysics probes, plus reductions to TESS, IXPE, NuStar, Astrophysics Research, Supporting Research & Technology, and Science Activation.

- Biological and Physical Sciences

- In: investigations planned for Artemis II and Artemis III, initial research to be conducted on future commercial space stations.

- Out: most research on the International Space Station, Center ground-based testing facilities, international collaborations.

- Earth Science:

- In: SWOT, SMAP, PACE, upcoming U.S.-Indian NISAR radar satellite, Grace-Continuity, Libera, future medium and small missions in the Earth Explorer and Earth Venture series, and restructured Landsat-Next.

- Out: Earth System Observatory missions including existing Terra, Aqua and Aura and upcoming AOS-Storm and AOS-Sky, Surface Biology and Geology Thermal Infrared Radiometer (SBG-TIR), and Visible & Shortwave Infrared Spectrometer (VSWIR), and existing SAGE-III, OCO-2, OCO-3, and NASA instruments on DSCOVR.

- Heliophysics:

- In: Space Weather Program, Heliophysics Explorer including MUSE, Living with a Star including continued support for Parker Solar Probe, Solar Dynamics Observatory, Voyager, upcoming IMAP and Carruthers Geocorona Observatory.

- Out: HelioSwarm, Extreme Ultraviolet High-Throughput Spectroscopic Telescope (EUVST, with Japan).

- Planetary Science

- In: Perseverance and Curiosity Mars rovers, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), NASA participation in ESA’s Mars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), Europa Clipper, Psyche, Lucy, upcoming NEO Surveyor, Dragonfly, and Mars Future Missions (lower cost missions and hosted instrument opportunities).

- Out: NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return mission, NASA participation in ESA’s Rosalind Franklin Mars rover, two existing NASA Mars satellites (MAVEN and Mars Odyssey) and NASA participation in ESA’s Mars Express, NASA’s two Venus missions (DAVINCI and VERITAS) and NASA participation in ESA’s Venus probe (EnVision), OSIRIS-APEX, Juno, New Horizons and activities in Planetary Science Research, Venus and Mars Technology, and Radioisotope Power Systems are reduced.

The proposal would create a Commercial Mars Payload Services (CMPS) program modeled after the Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative (CLPS). CLPS is being moved to ESDMD, which would also manage CMPS, although the hosted instruments in the Mars Future Missions line “will likely be delivered” via CMPS.

One common theme in the two directorates is the rupturing of international partnerships, particularly with the European Space Agency (ESA), one of NASA’s longest and most steadfast partners. From cancellation of Artemis’s international Gateway lunar space station (involving ESA as well as Japan, Canada, and the UAE) and Orion spacecraft (ESA provides the Service Module) to ending cooperation on Mars, Venus, and other international science projects, the changes are profound.

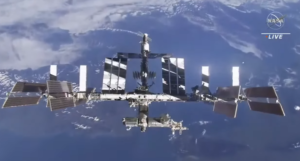

Added to that is NASA’s decision to phase down operations of the U.S.-Russian-European-Japanese-Canadian International Space Station much earlier than expected. ISS is managed in the Space Operations Mission Directorate (SOMD). While maintaining 2030 as the date for deorbiting the space-based laboratory, NASA will immediately reduce the number of crew and cargo flights to a minimal level. As part of its obligations under the Intergovernmental Agreement that governs the ISS program, NASA is responsible for launching Japanese, European and Canadian astronauts so there will be fewer flight opportunities for all.

Jim Zimmerman, who was NASA’s representative to ESA for 12 years and later an international space consultant and President of the International Astronautical Federation, told SpacePolicyOnline.com via email that the budget proposal “would have a devastating impact on NASA’s collaboration with countries around the world.” Program changes and cancellations are not new, “but never before have so many major NASA programs involving significant collaboration with international partners been impacted.” He expects NASA will still seek international cooperation in the future, but “partners will likely view these new opportunities in a different, far more cautious, fashion.”

SOMD also is charged with helping commercial companies build space stations to replace ISS — the Commercial LEO Development or CLD program. Instead of building another space station itself, NASA wants to be one of many customers purchasing services from companies that own them. Several companies are working with NASA already. The agency hopes at least one CLD will be operational before ISS is deorbited in 2030, just five years from now. The budget proposal calls for “rescoping” the Phase 2 CLD certification and services acquisition plan to speed things along, but the funding for the next three years when those companies may need it the most is modest: $272 million in FY2026, $302 million in FY2027 and $302 million in FY2028. It doubles to $602 million in FY2029 and FY2030.

The Space Technology Mission Directorate is completely reorganized so it’s difficult to follow the money, but like SMD its budget is cut about 50 percent and part of its funding has to pay for NASA’s share of the government’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, a fixed percentage of the extramural R&D budget. The Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate would lose more than one-third of its budget primarily associated with “green” aviation programs.

One of the many complaints about the budget proposal is how decisions were made and by whom. As with Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), the motivation seems to be merely slashing spending, not a strategic assessment of requirements or an evaluation of consequences.

NASA has been spared the drastic workforce impacts already affecting agencies like NIH, NSF and NOAA with only one small Reduction-in-Force (RIF) so far, but the budget numbers imply that will soon change. Former NASA Chief of Staff Mike French recently pointed out that absorbing the 40 percent reduction to Safety, Security and Mission Services (SSMS), an infrastructure and internal operations account, would require “a completely different organizational model” and RIFs.

A table in the NASA budget documentation shows a dramatic drop from 17,391 Full Time Equivalents (FTEs) in FY2025 to 11,853 FTEs in FY2026. A footnote adds for now they “should not be considered final or directly comparable to prior year allocations.” The acronyms refer to Headquarters (HQ), Ames Research Center (ARC), Armstrong Flight Research Center (AFRC), Glenn Research Center (GRC), Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), Johnson Space Center (JSC), Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Langley Research Center (LaRC), Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), Stennis Space Center (SSC), and NASA Shared Services Center (NSSC). OIG is the independent Office of Inspector General.

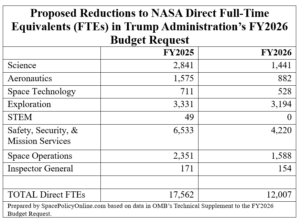

OMB’s 1,224 page “Technical Supplement” breaks the workforce changes down by theme. The total doesn’t exactly match the NASA document, but is close.

The budget proposal is just that, a proposal. Under the Constitution, only Congress decides how taxpayer money is spent. The Planetary Society among others is urging supporters to sign a petition to fight against the cuts as congressional deliberations get underway.

BREAKING: The Trump administration’s budget request just hit Congress and slashes NASA funding to its lowest level since 1961, which could usher in a dark age for NASA space science.

What happens next? Congress will make the final decision and set the budget. The good news: YOU… pic.twitter.com/1y1cFT4xW8

— Planetary Society (@exploreplanets) May 30, 2025

Congress was in recess on Friday afternoon when the budget proposal was released, but Rep. George Whitesides (D-CA), Vice Ranking Member of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, quickly called it “dead on arrival.” He was NASA Chief of Staff from 2009-2010 and then CEO of Virgin Galactic.

The administration just released its detailed plans for NASA’s budget next year.

Bottom line up front: this budget cedes our leadership to China and is dead on arrival.

Here are some of the takeaways from the proposal:

❌ Decimates the workforce

❌ Cancels dozens of existing…— George Whitesides (@gtwhitesides) May 31, 2025

Congressional appropriators have been waiting for the President’s proposal. Budget requests are supposed to be submitted on the first Monday in February. They rarely are, especially in a President’s first year, but this is the latest in history according to the top Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT). Appropriators have been holding a few hearings using the skinny budget with top-level numbers released on May 2. Neither the House nor the Senate have held a hearing on NASA yet, perhaps waiting to see when an Administrator would be confirmed.

Trump’s decision yesterday to withdraw Jared Isaacman’s nomination is a setback. Whoever leads NASA has to support the President’s budget request, but without a Senate-confirmed Administrator NASA is in a weaker position to explain to Congress the agency’s goals, challenges, and needs.

The House Appropriations Committee already scheduled a subcommittee markup of the Commerce-Justice-Science (CJS) bill that includes NASA for July 7 and full committee markup for July 10, so there are five weeks to go. Whether a replacement for Isaacman will be nominated and confirmed before then seems doubtful especially since they’ll be in recess one of those weeks for the July 4 holiday. Not impossible, but very unlikely.

Perhaps of more concern is that even under the best of circumstances Congress does not pass appropriations bills by the beginning of the fiscal year on October 1. With the request arriving this late, it is virtually impossible for FY2026. Congress wasn’t able to pass any of the 12 FY2025 appropriations bills at all. The government is operating under a Continuing Resolution (CR) that nominally funds agencies at their prior year levels.

Stakeholders and interest groups surely will be letting Congress know their views, but it’s not clear how much impact appropriators will have. Although Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power of the purse, the Trump Administration seems more than willing to test the limits. The White House wants to implement $9.4 billion DOGE spending cuts reportedly with or without congressional approval. In addition, on Friday Trump issued a sequestration order that on October 1, 2025 “direct spending budgetary resources for fiscal year 2026 in each non-exempt budget account be reduced by the amount calculated by the Office of Management and Budget in its report to the Congress of May 30, 2025.”

This article has been updated.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.