ESA Reacts to Proposed NASA Budget Cuts

The head of the European Space Agency responded to the Trump Administration’s proposed deep cuts to NASA programs today by saying ESA still wants to cooperate with NASA, but will be assessing alternative scenarios. The two space agencies have a long, extensive history of cooperation in human and robotic spaceflight that today includes the International Space Station, the Artemis program, and scientific missions like Mars Sample Return. All of those would be upended if the proposed cuts are enacted.

ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher said NASA briefed him about the budget proposal. ESA “remains open to cooperation with NASA on the programmes earmarked for a reduction or termination but is nevertheless assessing the impact with our Member States” as they prepare for a quarterly ESA Council meeting next month and the Ministerial Council meeting in November. The Ministerial Council, composed of the relevant Ministers from each of ESA’s 23 Member States, meets triennially to set ESA’s budget and program for the next three years.

It would be difficult to overstate the depth and breadth of NASA-ESA cooperation since ESA’s formation in 1975, and even before that with ESA’s predecessor, the European Space Research Organisation, ESRO.

ESA provided the Spacelab science module that flew inside the cargo bay of the U.S. space shuttle starting in 1983. In 1985, ESA was one of the first countries to sign up to participate in Space Station Freedom, now known as the International Space Station (ISS). ESA built ISS’s Columbus science module and provided five cargo resupply flights of the Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV). ESA is a partner in both the beloved Hubble Space Telescope and the newer James Webb Space Telescope, providing science instruments for both as well as Hubble’s first two sets of solar arrays and JWST’s launch.

Among the most prominent cooperative projects today are ESA’s continued participation in the ISS, the Artemis lunar program, and two robotic Mars missions –Mars Sample Return (MSR) and the Rosalind Franklin/ExoMars rover.

The Trump Administration’s budget proposal released on Friday would cut back crew and cargo flights to the ISS and limit research to only that which supports human exploration of the Moon and Mars. ESA crew members launch to the ISS primarly as part of NASA crews. Fewer NASA launches would mean fewer opportunities for ESA astronauts. ESA does have some flexibility in this case, however. ESA astronauts have flown on Russia’s Soyuz in the past and presumably could again. In addition, ESA and other European astronauts visit ISS for short durations as part of commercial space crews like Axiom-4, scheduled for launch later this month.

As for Artemis, the budget proposal would end the use of the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft after the third flight, Artemis III. ESA provides the service module for Orion, which ferries astronauts between Earth and lunar orbit. ESA also is a major partner in Artemis’s Gateway lunar space station where astronauts would transfer from Orion to Human Landing Systems to get down to and back from the lunar surface. Canada, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates also are Gateway partners. All of that would disappear if the budget proposal is enacted.

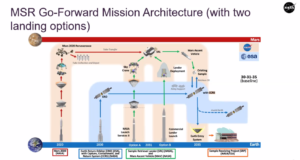

The budget proposal also would terminate MSR, which is designed to use an ESA-provided Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) to transfer samples being collected right now by NASA’s Perseverance rover back to Earth from Martian orbit.

The fate of NASA’s participation in ESA’s Rosalind Franklin/ExoMars mission wasn’t mentioned in Friday’s documents, but with the extensive cuts to NASA’s science program, many expect it also is on the chopping block. That project already has had a tumultuous history. In the early 2010s, NASA and ESA agreed to send two missions to Mars that included an ESA rover, but the Obama Administration cancelled NASA’s participation in 2012 because of budget constraints. ESA turned to Russia and they worked together with Russia building the ExoMars lander and ESA the rover, named Rosalind Franklin after the British chemist who played a key role in understanding the molecular structure of DNA.

The lander and rover were completely built and ready to be delivered to Russia’s launch site in February 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. ESA ended all space cooperation with Russia and turned back to NASA for help getting the rover to Mars. NASA is eager to do that and has been planning to provide the lander’s descent engines, radioisotope heaters, systems engineering and entry-descent-landing (EDL) support, and a science instrument, MOMA, built in collaboration with European scientists.

International cooperation is the foundation of ESA’s existence. It has 23 member states: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Latvia and Lithuania are Associate Members. Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Malta have cooperation agreements, and Canada sits on the ESA Council and participates in some projects.

International cooperation also has been a hallmark of NASA’s existence since it was created in the 1958 National Aeronautics and Space Act. Section 205 directs NASA to “engage in a program of international cooperation in work done pursuant to the Act, and in the peaceful application of the results thereof…”

For all the international successes over the decades, this isn’t the first time a U.S. President has suddenly changed direction with serious consequences for partners like ESA.

Like Trump, Ronald Reagan in his first year in office, 1981, directed steep cuts to NASA’s science program, including ending NASA’s role in the International Solar Polar Mission (ISPM). Two spacecraft, one from NASA and one from ESA, were to orbit the Sun making simultaneous measurements over the North and South poles. ESA went ahead with its spacecraft, Ulysses, with NASA providing a radioisotope power source, launch, and tracking services, but learned a hard lesson about the vagaries of cooperating with the United States. That lesson hasn’t been forgotten and has been amplified over the years by multiple changes to the ISS program, like suddenly bringing Russia in as a partner during the Clinton Administration, and Obama cancelling the robotic Mars missions in 2012.

ESA’s space capabilities have grown immeasurably over the past five decades and its theme these days is the need for autonomy in space. The recently released ESA Strategy 2040 lists “Strengthen European Autonomy and Resilience” as the third of its top five goals. If the proposed changes to NASA’s portfolio are enacted by Congress, autonomy may rise higher in the list to the detriment of U.S. civil space aspirations. As Aschbacher points out, “space exploration is an endeavor in which the collective can reach much further than the individual.”

Trump spoke glowingly of the NASA-ESA Hubble Space Telescope a week and a half ago and said he is “committed to ensuring that America continues to lead the way in fueling the pursuit of space discovery and exploration.” Hopefully he will come to appreciate the importance of international partners in that pursuit.

Reagan did. Three years after killing ISPM, he directed NASA to build a space station — with international partners.

Tonight, I am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade. …

We want our friends to help us meet these challenges and share in their benefits. NASA will invite other countries to participate so we can strengthen peace, build prosperity, and expand freedom for all who share our goals. — Ronald Reagan

In collaboration with Japan, Canada, Russia, and 11 European countries working through ESA, that’s just what NASA did. The International Space Station is about to reach 25 years of permanent occupancy with international crews conducting a broad range of scientific experiments and learning how to live in microgravity as a prelude to trips to Mars.

Aschbacher said ESA will be looking at alternatives as the United States decides whether the budget proposal will become budget reality. NASA’s other partners likely are doing the same thing. And alternatives there are. ESA is stepping up its own efforts to participate in building commercial space stations to succeed the ISS and commercial cargo transportation services. China already has a space station and plans to send taikonauts to the Moon by 2030, welcoming international participation. It also plans to launch a robotic Mars sample return mission in 2028.

Since 1958, the United States has led the world in opening space to participation by other countries and benefiting from their contributions. As Congress weighs the Trump Administration’s budget proposal, it will have to bear in mind the impact of the proposed cutbacks not only on NASA, but on the international partnerships the United States has so carefully crafted and nurtured over the decades. Aschbacher made it clear ESA wants to continue being a reliable, strong and desirable partner with “space agencies from around the globe.” The question is whether the United States still has the same goal.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.