NASA IG Worries About Lack of Redundancy for ISS Operations, Longer Term Issues

NASA’s Office of Inspector General gives NASA pretty good marks for how it is managing the risks of continued operation of the aging International Space Station, but is worried about the current lack of redundancy in crew and cargo transportation systems. Delays in Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule and Northrop Grumman’s need to build a new rocket to launch its Cygnus cargo spacecraft means that SpaceX has the only U.S. rocket capable of delivering people and supplies right now. The OIG also is concerned about several other issues including the air leak in a Russian module and transition planning for the post-ISS era.

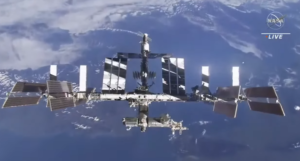

Construction of the ISS began in 1998 and the Earth-orbiting laboratory has been permanently occupied by international crews rotating on roughly 6-month missions since November 2000. A partnership among the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada and 11 European countries working through the European Space Agency, the current plan is to deorbit the ISS at the end of this decade when at least one commercial space station is expected to be available to replace it.

Until then, the ISS must be routinely resupplied with cargo and crews and the crews must be as safe as possible while they’re aboard.

The new NASA OIG report gives NASA credit for how it is managing the risks: “we found the ISS Program is well positioned to continue operations and maintenance of the ISS through 2030.”

However, a near-term concern is that despite NASA’s efforts to have two independent U.S. systems to deliver cargo and rotate crews — dissimilar redundancy — they don’t have it at the moment.

When permanent ISS occupancy began, the U.S. space shuttle and Russia’s Soyuz were the two systems that could ferry crews back and forth. The shuttle was also used to deliver cargo along with Russia’s Progress and in later years ESA’s Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) and Japan’s H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV).

The 2003 space shuttle Columbia tragedy changed everything not only because of the immediate consequences — Russia’s Soyuz was used to transport Russian and U.S. crews until shuttle flights resumed in 2005 — but President George W. Bush’s 2004 directive to terminate the shuttle as soon as ISS construction was completed. The decision was based both on concerns about shuttle safety and to free up money to pursue Bush’s goal of returning astronauts to the Moon by 2020 (the Constellation program).

That meant NASA had to come up with new crew and cargo transportation systems to replace the shuttle after its final flight in July 2011. The agency did that through Public-Private Partnerships where the government and the private sector share development costs, but the companies retain ownership of the systems and NASA purchases services from them.

Over time that led to two cargo delivery systems — SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon and Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus — that are in service today. Another company, Sierra Space, is getting ready to introduce a third, Dream Chaser, but the inaugural launch has been repeatedly delayed.

Cargo Dragon launches on SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Cygnus usually launches on Northrop Grumman’s Antares rocket, but Antares was built with Russian and Ukrainian hardware that is no longer available. A new version is under development by the U.S. company Firefly. Until it’s ready, Northrop Grumman is buying launch services from SpaceX.

That’s the source of the OIG’s concern — all U.S. cargo deliveries to the ISS are currently dependent on Falcon 9.

That will change once the new Antares is available and Dream Chaser starts flying (it will launch on a United Launch Alliance Vulcan), but until then Falcon 9 is the only rocket that can deliver U.S. cargo to the ISS. ESA’s final ATV launch was in 2014 and Japan has not launched an HTV since 2020 while an upgraded version that will launch on Japan’s new H3 rocket is in development.

Falcon 9 is a very reliable rocket, with only two launch failures in more than 370 attempts, but failures do happen. The first Falcon 9 failure, in fact, was a cargo delivery flight to the ISS in 2015. The second was in July and SpaceX quickly diagnosed and remedied the program, resuming flights just two weeks later. SpaceX recovers most of the Falcon 9 first stages and a landing failed last month, but overall Falcon 9 has an impressive record. Still, it’s a risk to be dependent on a single rocket even temporarily.

NASA also is dependent on SpaceX and Falcon 9 for crew transportation to the ISS. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon is used for NASA-sponsored flights to the ISS that carry not only NASA astronauts, but those from other ISS partner countries including Russia.

Roscosmos and NASA routinely launch each other’s crew members to ensure that at least one from each country is aboard the ISS at any given time to operate the interdependent Russian and U.S. segments. In a sense, Russia’s Soyuz is a redundant crew transportation system for NASA and Crew Dragon is a redundant crew transportation system for Roscosmos, but each country wants its own national system.

In NASA’s case, it wants two to ensure that American astronauts can launch on American rockets from American soil, unlike the nine years between the end of the shuttle program and Crew Dragon’s first flight in 2020 during which it had to pay Russia higher and higher prices for crew transportation services.

NASA contracted with Boeing in 2014, the same time as SpaceX, to build the other U.S. system, Starliner, that launches on ULA’s Atlas V. But repeated problems have delayed its operational debut. The Boeing Starliner Crew Flight Test this summer ended earlier this month when the capsule returned to Earth empty because NASA was concerned about the spacecraft’s propulsion system. NASA must certify Starliner as safe for NASA astronauts before operational flights commence and the agency has said the earliest that will happen is August 2025. Until then, as with cargo, NASA is reliant on SpaceX and its Falcon 9 rocket.

As a result of the delays in availability of Starliner, NASA had to move up previous contracted flights with SpaceX earlier than planned, costing the Agency an additional $17 million to meet expedited launch needs. It is not clear at this point whether additional SpaceX contracted flights will need to be accelerated and at what costs.

The long-delayed redundant commercial cargo and crew transportation options heighten the risks associated with a single launch provider for cargo and crew and may disrupt planned ISS operations. — NASA Inspector General

The OIG report also focuses on longer term issues for the ISS over the remaining years of its lifetime and what happens at the end. One is the need to develop a U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) to safely send it into an unoccupied area of the Pacific Ocean, for which NASA also has chosen SpaceX. NASA wants to launch the USDV in 2029, a year before the planned deorbit, and is confident SpaceX can get it ready in time since it is based on the Dragon design.

The OIG isn’t as optimistic citing both budget and schedule risk. In particular it finds the 5-and-a-half year development schedule to be “unrealistic” considering that historically such programs take “about eight and a half years from contract award to first operational flight.”

Added to that, deorbiting the ISS requires that Russia continue to participate in the ISS program until the end since Russia provides the propulsion needed to continually reboost the space station and maintain its correct altitude. But Russia is only committed to space station operations through 2028, not 2030. NASA is confident Russia eventually will agree to the 2030 date, but the OIG concludes that “without commitment from Russia to the deorbit plan, the ability to conduct a controlled deorbit is unclear.” Added to that, the OIG notes that the commercial space stations NASA wants to have in operation before the ISS is deorbited may not be ready in time. If NASA decides to extend ISS operations beyond 2030 either because the USDV or the commercial space stations aren’t ready, Russia’s continued participation would further be required.

Another OIG concern is the ISS’s structural integrity. Although some modules are relatively new, the first two were launched in 1998 and most of the others in the subsequent 10 years.

A compartment or “tunnel” that connects Russia’s Service Module to one of its docking ports began leaking several years ago. NASA and Roscosmos monitor it diligently and are convinced it doesn’t pose a threat to the ISS or the crew. Many attempts have been made to find and seal several individual leaks with some success, but then-NASA ISS Program Manager Joel Montalbano said in February that the leak rate had increased. NASA ISS Program Manager Robyn Gatens has said that she’s not overly worried because in a worse case scenario they could permanently close the hatch and simply lose access to that docking port.

The OIG is concerned, however. The report says that in May and June, NASA’s ISS Program elevated the “leak risk to the highest level of risk in its risk management system.”

“According to NASA, Roscosmos is confident they will be able to monitor and close the hatch to the Service Module prior to the leak rate reaching an untenable level. However, NASA and Roscosmos have not reached an agreement on the point at which the leak rate is untenable.” NASA IG

While permanently closing the hatch is a solution, that would mean one less port for cargo delivery and “Closing the hatch permanently would also necessitate additional propellant to maintain the Station’s altitude and attitude.”

Although just released on September 26, the OIG report was completed in July. At a briefing yesterday in connection with the upcoming launch of Crew-9, Gatens said since then the leak rate has decreased “by about a third” as the Russian cosmonauts continue making repairs.

Other issues highlighted in the report are the effects on the ISS of micrometeorioids and orbital debris (MMOD), which NASA itself considers “a top risk to crew safety,” and the limited options available to evacuate the ISS in an emergency.

The report makes four recommendations and NASA concurred with all of them (NASA’s response is published as an appendix).

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.