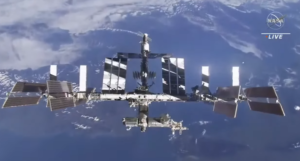

NASA Safety Panel Worried About Aging ISS, Need for Successor

NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) said today the International Space Station has entered its “riskiest period” as the root cause of persistent air leaks in the Russian segment remains elusive. To assure there is no gap in the U.S. ability to conduct research in low Earth orbit, they stress NASA must move forward expeditiously to facilitate commercial space stations to replace the ISS by the end of this decade. They are upbeat about the Artemis lunar program, though, seeing “no showstoppers” for the Artemis II launch a year from now, although there is a lot of work to go for Artemis III.

In their quarterly public briefing, the group was generally positive about the state of safety at NASA. Created by Congress after the 1967 Apollo fire, ASAP reports both to Congress and NASA with findings and recommendations on anything safety-related at the agency.

Meeting at Johnson Space Center for the second time in a row, human spaceflight was a main theme. The panel shared their reflections on the International Space Station (ISS) and Artemis programs, but largely demurred on the commercial crew program asserting that the information couldn’t be publicly released. They did observe, however, that the recent problems with Boeing’s Starliner Crew Flight Test could offer lessons-learned about government-contractor relationships in an era of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Praising the NASA team that operates the ISS, especially ISS Program Manager Dana Weigel, ASAP said they make the “very high operations tempo” look easy even though it is anything but that. ASAP’s Richard Williams believes “the ISS has entered the riskiest period of its existence.”

They are especially concerned about the air leaks in the Russian segment that began in 2019 and the lack of a common understanding between the Russian and American sides as to the source. Williams called the underlying cause “elusive” and said NASA and their Russian counterparts will meet again in Moscow this month to discuss how to mitigate risks. “The panel considers this one of our highest concerns.”

ASAP is also worried about the plans to deorbit the ISS at the end of the decade. The ISS is a partnership among the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, and 11 European countries operating through the European Space Agency. All but Russia have agreed to operate the ISS until 2030. Russia has agreed only to 2028, but NASA expects them to extend their commitment to 2030 in due course.

The 420-Metric-Ton facility needs to be deliberately deorbited into the Pacific Ocean or debris could land anywhere on Earth between 51.6ºN and 51.6ºS latitude, the orbit in which it flies. SpaceX is building a U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) to do that. USDV is to be delivered in 2028 and launched in 2029, but what if ISS can’t last that long?

“The risk to the public from ISS breakup debris will increase by orders of magnitude,” Williams said. The U.S. and Russia are working together to achieve a safe deorbit capability “both for end of life as well as a risk-managed deorbit for contingencies.”

Whenever ISS ends operations, the question is what comes next. NASA does not want to build another space station. Instead it wants to be just one of many customers purchasing services from companies operating commercial space stations. NASA initiated the Commercial LEO Development (CLD) program several years ago to establish PPPs with several companies to assess market viability during Phase 1 of the effort.

ASAP said preparations for Phase 2 are ongoing with an Industry Day planned for next month, a draft Request for Proposals (RFP) in the third quarter of 2025, a final RFP later in 2025 or early 2026, and the Phase 2 award in summer 2026. That would lead to Initial Operational Capability (IOC) in December 2029, a continuous crew presence in December 2030, and Full Operational Capability (FOC) in December 2031.

All of that requires issuing contracts in a timely manner, supporting an “entire ecosystem” including crew and cargo transportation, and ensuring human safety requirements are met. “There is no time to waste,” said ASAP’s Mark Sirangelo, urging everyone to “recognize the urgency.”

The big issue is money, both to operate ISS and ensure a “seamless transition” from ISS to the CLDs.

“Overarching all of these risks is a large ISS budget shortfall. All of these risks are actually a derivative of this budget shortfall and collectively contribute to potential compromise of the Low Earth Orbit transition plan. This might lead to a gap in LEO capability, which in turn leads to compromise of risk mitigation research in LEO, and this cascades to increased risk in the Moon to Mars exploration efforts. As the panel noted in its 2024 annual report, the ISS is also critical to human research necessary to enable the long duration spaceflight on which the Moon to Mars program rests. This work is not optional, but absolutely critical for safety of spaceflight. — Richard Williams

The PPPs that underpin CLDs and many aspects of the Artemis program began with the commercial cargo and commercial crew programs to support the ISS after the decision was made to terminate the space shuttle program in 2004. PPPs are fixed price contracts where the government and private sector share development costs, but the company retains ownership and sells services to NASA and other customers. The government has less oversight than with traditional cost-plus contracts, but expects to save money.

The commercial crew program has gotten a lot of attention over the past 10 months because of problems with Boeing’s Starliner Crew Flight Test (CFT) that meant two NASA astronauts, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, ended up staying on the ISS for nine months instead of eight days. Starliner has encountered many challenges since its first uncrewed test flight in 2019 and ASAP has been a useful and often only source of information about the spacecraft during that time.

Today, they demurred, saying only that they had “informative discussions” about the commercial crew program, including Starliner, “most of which are not publicly releasable.” ASAP’s Paul Hill did say ASAP offered NASA some advice, though.

“Characterizing contractor teams performing on what are called commercial service contracts as partners rather than as vendors leads to a very strong bias to be supportive of the partner. The panel urges the Commercial Crew Program to study this effect, and program management lessons-learned that [could] have led to problems being detected much earlier and could have influenced better contract performance. These lessons will be critical to future procurements implementing a similar commercial services contract structure. — Paul Hill

NASA’s progress on the Artemis program to put astronauts back on the Moon mostly won kudos. ASAP declared “we see no showstoppers at this time” for Artemis II, the crewed test flight of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft. In the spring of 2026, Artemis II will send four astronauts (three Americans, one Canadian) around the Moon for the first time since Apollo 17 in December 1972.

Artemis II will not go into orbit around the Moon, much less land. That will happen on the next flight, Artemis III, planned for mid-2027. ASAP was generally positive about the status of that mission, too, which requires not only SLS and Orion, but Axiom Space’s lunar spacesuits and SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System (HLS). Both are being developed through PPPs. The spacesuits are moving forward to Critical Design Review. Starship continues flight tests, although the last two (IFT-7 and IFT-8) exploded over the Caribbean.

ASAP’s worry isn’t the flight test failures per se, but for SpaceX to demonstrate the necessary launch cadence needed for missions to the Moon. Starship can only reach Earth orbit. To travel further, it must be refueled at an Earth-orbiting depot. Fuel depots do not exist in Earth orbit yet, and transferring cryogenic propellants in microgravity hasn’t been demonstrated. SpaceX has not said precisely how many Starship flights will be needed to fill the depot — “10-ish” is the best estimate they’ve offered — and they have to happen quickly because the propellant evaporates, a process called boiloff.

ASAP member Bill Bray said Starship launch cadence is the “biggest risk” for Artemis III.

“As the panel observes Artemis III execution, it does see the biggest risk for that event as the ability to manage and mitigate required launch cadence with respect to the propellant aggregation.” — Bill Bray

SpaceX is one of two companies that have PPPs to build Human Landing Systems for Artemis. NASA wanted two service providers for redundancy and competition. SpaceX has the contract for Artemis III and Artemis IV. Blue Origin has it for Artemis V with its Blue Moon Mark 2 lander that will be launched on its New Glenn rocket. Bray said ASAP was glad to see New Glenn launch for the first time in January and expects the next “in the June timeframe.”

Artemis is part of NASA’s Moon-to-Mars (M2M) program and ASAP is pleased with NASA’s management of the program now that it has a single director, Amit Kshatriya, to integrate the “complex” architecture. ASAP Chair Lt. Gen. Susan Helms (Ret.), a former NASA astronaut, said “we see incredible advantage with the current organizational arrangement of having a single program manager on top” with the right authorities and responsibilities “who looks across the entire integrated picture.”

NASA resisted creating a single, overarching M2M program office, but Congress required it in the 2022 NASA Authorization Act.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.