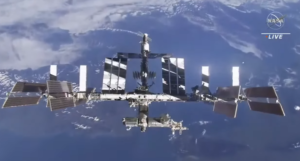

NASA: ISS Deorbit Vehicle Will Cost $1.5 Billion, but It’s Essential

NASA and SpaceX are providing more details about the spacecraft SpaceX will develop to safely send the International Space Station to a watery grave about 6 years from now. The U.S. Deorbit Vehicle is based on SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon, but will be much more powerful so it can control the 420 Metric Ton conglomeration as it breaks apart descending through the atmosphere. NASA is still working on getting Congress to approve the $1.5 billion needed to build and launch the USDV, but they have clearance to proceed and will take the money from elsewhere in their budget if necessary.

Until recently, NASA and its ISS partners — Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, and the European Space Agency — planned to use three Russian Progress cargo spacecraft to deorbit the ISS at the end of its lifetime.

NASA now says the partners have concluded that the Russian segment of the ISS is not designed to manage three Progresses firing at the same time. Another solution is needed to ensure the football field-sized assemblage of U.S., Russian, European and Japanese modules, Canada’s robotic arm, and all the equipment needed to support crews living aboard it on a permanent basis since November 2000 safely reenters with any surviving pieces falling harmlessly into the ocean.

The news that Progress would not be used came after Russia invaded Ukraine. Just three weeks before the February 24, 2022 assault, NASA issued an ISS transition plan specifying the use of Progress for deorbiting the ISS in 2031.

The U.S.-Russian relationship quickly deteriorated and doubts arose about Russia’s long term commitment to the ISS partnership. Offensive statements by the then-head of Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin, exacerbated tensions, but the tenor improved when he was replaced by Yuriy Borisov and ISS remains one of the few vestiges of friendly U.S.-Russian relations. Russia later agreed to continue operating the Russian segment until 2028, but the other partners have agreed to keep their portions functioning until 2030. NASA is confident Russia will extend to 2030 when the time is right, but the question of how to deorbit ISS has taken on new urgency.

During a media telecon yesterday, NASA ISS Program Manager Dana Weigel couched last year’s seemingly abrupt decision to ask Congress for what was then $1 billion to build a U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) in the context of a joint decision based on a revised analysis of Progress’s capabilities, however.

“Early on in station planning, we had considered doing the deorbit through the use of three Progress vehicles, but the Roscosmos segment [of the ISS] was not designed to control three Progress vehicles at one time so that presented a bit of a challenge and also the capability wasn’t quite what we really needed for the size of station. So we jointly agreed together to go have U.S. industry take a look at what we could do on our side for the deorbit.” — Dana Weigel

NASA issued a Request for Proposals from U.S. industry and on June 26 chose SpaceX to build the USDV for $843 million. That does not include launch or other costs like integrating it onto the launch vehicle. Ken Bowersox, who heads NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate (SOMD) that oversees ISS, said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson is now seeking $1.5 billion to cover it all.

NASA wants to launch the USDV one-and-a-half years before ISS is deorbited, which would put launch in the 2029 time frame, just five years from now. The decision to build a USDV unfortunately has coincided with congressional determination to cut federal spending, especially non-defense spending like NASA. NASA requested $180 million for the USDV in FY2024, but Congress approved none as it cut the agency by more than $2 billion compared to the request. Worried that might happen, Nelson convinced the Biden Administration to include the money in a separate domestic supplemental request submitted to Congress at the end of last year, but there has been no action on it.

Nelson has been pleading with Congress to provide the money, but Bowersox said if new money is not forthcoming, the USDV is so important they will have to take money from other parts of the SOMD budget, “which could affect ISS operations.” Asked how much money they have for the current fiscal year, FY2024, he said they’re still waiting for action on the supplemental, but were able to allocate a small amount of money to this in FY2023.

“We were able to get a small amount put into the previous year’s appropriation, so we have clearance to move ahead with the program and the next step is to try and get full funding if we can. … We’ve asked for, in a supplemental, $180 million … but if we don’t get that this is important enough to us that we’ll have to take it out of our current funding and it could affect ISS operations.” — Ken Bowersox

NASA’s FY2023 operating plan, which it submits to Congress to show how it plans to spend the money that was appropriated, shows $10 million for an ISS deorbit vehicle. The FY2025 request is $109 million.

He added Congress and the Executive Branch are supportive and NASA is remaining patient as the process plays out.

A former astronaut, Bowersox was commander of ISS at the time of the February 2003 space shuttle Columbia tragedy and spent extra weeks there as NASA and Roscosmos figured out how to continue getting crews back and forth with only Russia’s Soyuz.

Some ISS advocates have been trying to convince NASA to boost the station’s orbit instead so it can remain in space as a historical artifact, offer industry the opportunity to take all or parts of it for new space stations, or bring back major components to be put on display in museums.

Bowersox allowed that he also has great fondness for the ISS. “The emotional part of me would love to try and save some of ISS, but the practical part of me realizes that using something like the USDV and bringing it safely back into the ocean somewhere is the most practical approach.” As for boosting the orbit, he pointed to the debris hazard ISS would pose. “The responsible thing we believe right now is to go ahead and bring ISS home.”

As for turning it over to someone else, Weigel noted that NASA doesn’t own all of it. Each partner has contributed modules or other hardware like Canada’s robotic arm so NASA doesn’t have the authority to give it away.

They will try to save some items for historical purposes that can be brought down on the vehicles that already return to Earth like SpaceX’s Crew and Cargo Dragons and Russia’s Soyuz. No decisions have been made on exactly what, but Bowersox mentioned the ship’s bells, logs, and wall panels with mission patches as examples.

The rest of it, however, is destined for reentry. In the Janauary 2022 ISS transition plan, NASA identified the South Pacific Uninhabited Area around Point Nemo as the final resting place for any chunks that survive, but Weigel now says they haven’t decided where. The Indian Ocean is an option.

NASA’s first space station, Skylab, reentered over the Indian Ocean in 1979. Skylab was much smaller than ISS and was not designed with a deorbit capability. It made an uncontrolled reentry with some pieces landing in western Australia. NASA wants to avoid a similar fate with ISS and has more recent experience with a small piece of an ISS battery pallet that unexpectedly survived reentry and fell through the roof of a home in Florida. No one was hurt, but the homeowner is suing NASA for damages. Pieces of several reentering SpaceX Dragons also have unexpectedly survived reentry and been recovered on Earth.

NASA realizes parts of ISS will make it through reentry with surviving pieces ranging from the size of a microwave oven to an SUV. They will fall into what Weigel described as a “tight footprint” in the ocean about 2,000 kilometers long.

The USDV will be the chariot for ISS’s final days. Unlike the Commercial Crew and Commercial Cargo programs where NASA purchases services from SpaceX and other suppliers, the USDV is a more traditional procurement. SpaceX will deliver it to NASA and NASA will own, launch and operate it.

Sarah Walker, head of SpaceX’s Dragon program, explained some of the modifications that will be made to the existing Cargo Dragon to enhance the spacecraft’s capabilities for this unique mission.

The Service Module section (with the solar arrays) will be twice the size of a typical Cargo Dragon with six times the propellant and four times the power. It’ll have a total of 46 Draco thrusters, 30 of them for making maneuvers. As many as 22-26 will fire at the same time enabling a “delta V,” or change in velocity, of 57 meters per second, the requirement set by NASA. The total mass of the spacecraft will be about 35,000 kilograms, of which 16,000 kg is propellant.

Asked why SpaceX didn’t propose Starship as the USDV, Walker said the massive vehicle has too much thrust for this application.

NASA will begin procurement of a USDV launch vehicle three years before launch. The amount of mass is too much for SpaceX’s Falcon 9, but Falcon Heavy, ULA’s Vulcan, or Blue Origin’s New Glenn could be among the potential bidders.

The current plan is to deorbit ISS in January 2031, which means launching the USDV in 2029. The final ISS crew exchange will take place just before that launch. They’ll remain aboard while the USDV is checked out and the ISS is allowed to begin drifting down. The crew will leave when the ISS reaches 330 kilometers. After that it will continue its natural decay over the course of the next six months. When it reaches about 220 kilometers, the USDV will be activated. The rest of the ride down will be turbulent and the USDV has to stay in control, completely autonomously. It will not be able to depend on ISS power or communications systems for the last four days.

NASA hopes and expects that at least one new commercially developed low Earth orbit (LEO) space station will be operating by then. NASA plans to purchase space station services from commercial providers in the future instead of owning and operating LEO space stations itself. Avoiding a gap between ISS and a commercial LEO space station is important both because NASA needs access to a LEO space station for its own research and the United States does not want China to be the only country with a space station orbiting Earth.

The date for ISS to be deorbited could change if the commercial space stations are delayed. NASA is working with three companies — Axiom Space, Blue Origin, and Starlab (a joint venture between Voyager Space and Airbus) — but many issues remain unresolved.

User Comments

SpacePolicyOnline.com has the right (but not the obligation) to monitor the comments and to remove any materials it deems inappropriate. We do not post comments that include links to other websites since we have no control over that content nor can we verify the security of such links.